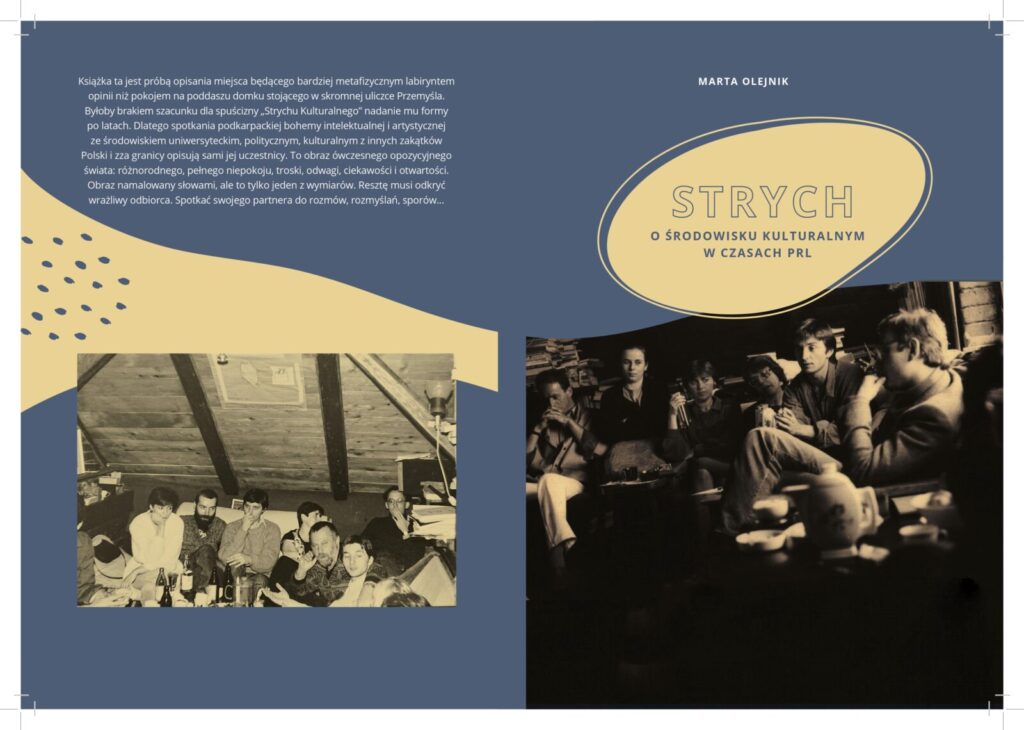

This book is an attempt to describe a place which is more of a metaphysical labyrinth of opinions than a room in the attic of a house standing in a modest street of Przemysl. It would be disrespectful to the legacy of the "Cultural Attic" to give it a form years later. That is why the meetings of the Podkarpacie Bohemia intellectual and artistic community with university, political, and cultural circles from other parts of Poland and abroad are described by its participants themselves. This is a picture of the then opposition world: diverse, full of anxiety, care, courage, curiosity and openness. A picture painted in words, but this is only one dimension. The rest must be discovered by a sensitive viewer. To meet one's partner for conversations, pondering, disputes...

INTRODUCTION

The attic is associated with a mysterious place, slightly hidden from an accidental visitor. At the same time it arouses curiosity about what it hides, it is a promise of something forbidden, an oasis of things, thoughts, imagination that have stopped for a moment in their journey between the real world. The experiences gathered in the attic gain a new meaning and return to people again. This is what the "Cultural Attic" was like: an underground magazine that was created in the attic, in the heads of people seeking shelter from the unfriendly world.

The name of the magazine referred to the heritage of generations; dusty, abandoned somewhere in the attic, but without which the view of the community would be incomplete. For some, it was an opportunity to encounter art, a new thought, an idea for others. The Attic is not only the name of a literary and artistic magazine, it is also a meeting place for a group of friends creating an independent cultural circuit. It was an adapted attic of a single-family house, filled with artists' works, paintings, books, which overlooked the surrounding hills. In front of the house there was an old orchard of deciduous apple trees with an unmowed meadow. Lots of greenery everywhere. "From the perspective of the attic we looked at the world around us, not forgetting the existence of the underground. We lived a somewhat dualistic life: working, taking care of everyday matters according to the communist rules, but spiritually apart," wrote Marek Kuchciński, the attic's host and one of the magazine's editors, in the introduction to the reprint. ("SK" was also edited by Jan Musiał, Mirosław Kocoł, and later by Mariusz Kościuk).

Professor Jarosław Piekałkiewicz, for example, is not afraid of bold comparisons: The attic had more significance than it appears at first glance. The atmosphere of these gatherings reminded me of my gatherings in the Home Army. In the attic, as in the Home Army, we felt free. Of course, during the war, we risked much more, because of torture and death, but for us, as for the members of the Attic, "Poland is not yet lost while we live." The members of the Attic risked persecution by the Communist authorities, perhaps even arrest, and certainly difficulties in their careers. Like us in the Home Army, they were a minority, because the majority of Poles believed that one must live.

"The Cultural Attic" remains a symbol to this day. There is not a serious expert in the history of culture and politics of the 1980s in Poland who would not see the "Attic" as a change. It did not ignite the flame that consumed the entire communism, but it was one of the sparks that ignited the individual and collective imagination. Even Marek Kuchciński's greatest opponents admit that he was able to create a place in Przemyśl, on the outskirts of postwar Poland, that gave a sign to others: "We can reach further", attracting well-known thinkers, giving faith to young activists. Since it worked in Przemyśl, which was closer to the wild Bieszczady Mountains than to the salons of big-city sofas and big-industry workers' movements, why not make the Solidarity revolution somewhere else? Make it more attractive with a deeper reflection on the human being, his or her place in culture and history, and the various expressions of rebellion.

When we think about opinion formation today, we immediately embrace the current reality of the information bubble. As a society we are divided into small groups. We set up ideological frames for ourselves, and they are also imposed by technology. Today, views are largely formatted by the soulless algorithms of internet information filtering systems. They are meant to keep us in a zone of intellectual comfort, meeting predefined needs. In the 1980s, Przemyśl did not have such a framework, thanks to which independent culture could meet in one place with the agricultural opposition and the underground Solidarity movement. The deeply Catholic intelligentsia found common ground with the farmer, whose main concerns were the controlled purchase of pigs and the coarse reality of the state farm. The melting pot of influences mixed the passions of hippie rebels with pastoral admonitions Ignacy Tokarczuk, Bishop of Przemyśl. Traditional Polish religiousness clashed with the logic of Wittgenstein's ambiguous faith.

Thus, one can say that this study is not about unequivocally capturing what really happened in the attic of a small house on the outskirts of Przemyśl. It will always remain an interpretation of the people who were there. Because they were there for different reasons, they followed different paths and this was the strength of this place. Today, the attic is also judged by the person of its host. A man as difficult to assess unambiguously as the "Cultural Attic" itself. Marek Kuchcinski - the Speaker of the Sejm, one of the most recognizable politicians of the party that has ruled continuously since 2015. Or maybe, however, the man from the attic, a dreamer hunched over a typewriter, surrounded by books and craving freedom during long solitary wanderings in the Bieszczady Mountains. This second face is almost unknown. A drummer in avant-garde art engaged in the scene followed by Grotowski, and - let us imagine such an Arcadian image - a hippie running around a meadow in Lublin, picking cornflowers and corn ears to make a field bouquet for his friends who fed him with Russian dumplings.

Kuchciński made his strongest mark not only because he was the host of the attic - in fact he did not run the magazine himself - but also because he had a gift for organisation. He was able to convince whoever he needed to find a duplicator, he knew how to pull a ream of paper out of the ground. He combined stubbornness with courage. He was not known for politics in the underground Solidarity movement. In the Silesia and Podkarpacie regions it was known, however, that if it was necessary to transport someone threatened with internment, it was enough to talk to Marek, because he was able to get people wanted by the SB out of a moving train. Kuchciński was valued by bishops and "ordinary" priests. However, he usually preferred to stay in the shadow. "Strych Kulturalny' also tended to refer to the intellectual legacy, drilling the interlocutor's consciousness with names of philosophers and historians.

It is difficult to clearly define what the "Cultural Attic" was and what impact it had on the consciousness of many people. Professor Krzysztof Dybciak, a literary historian and theoretician, essayist, and author of poetry, recalls the cultural events, sometimes called "attic meetings," and issues of the magazine: "They were original phenomena on the map of independent culture existing outside the structures of the communist-ruled state. One of the unusual features was the phenomenon of attracting collaborators not only from Poland. At the time, it was truly exceptional for so many British artists and intellectuals to perform in a small (by European standards) town right on the border of the Evil Empire. And Przemyśl hosted not just any artists; Professors Mark Lilla and Roger Scruton are important figures in the world's humanities. And yet, knowledge of such a valuable phenomenon of free culture in the 1980s is scant.

Marta Olejnik