The year 1989 was marked above all by the June elections. Although not fully free and involving many compromises, they nevertheless brought great hope and energy. In anti-communist Przemysl, there were no problems with collecting signatures for the Solidarity list. Despite doubts about the Round Table Agreements, people believed that new, good times would come. The previous reluctance to vote in the rigged elections to the Communist-era Sejm turned into enthusiasm that new people would finally sit in parliament. The candidates from the Solidarity side had a program that was talked about at home, at work, and on the street. On the list carrying a breath of freedom were people who gave hope that the Polish state, so far subordinate to the USSR, would regain its longed-for freedom.

Marek Kaminski, chairman of the Regional Executive Commission of the Solidarity Trade Union in Przemyśl, was obliged by the National Executive Commission to establish, together with the local Solidarity of Individual Farmers, a Solidarity Civic Committee for the Przemyśl voivodeship. Together with the head of the Agricultural Solidarity, Jan Karus, he invited 15 people, including Marek Kuchciński, to join him.

However, folks, the program is not everything. The old power held firm. It had full control over the state media, the whole propaganda apparatus. In order to reach the people, the pro-independence message had to be directed directly to the street.

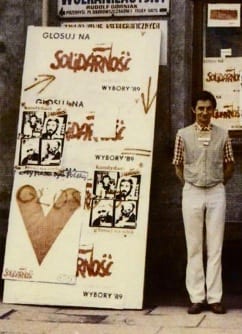

- In June 1989 Przemyśl was probably the city which was most overburdened with election banners of the Solidarity opposition and posters in all of Poland", remembers Marek Kuchciński. - From the very first days of the campaign there was a poster war in the cities and villages - new posters and banners, usually destroyed at night, were being replaced with new ones. One of the leaflets, the so-called "how to cross out your opponent" was reproduced in the underground printing house in the amount of 300 thousand copies. In such an atmosphere the opponent, whose coalition office was supposedly headed by a censor from Przemyśl, not only had no chance to win, but also compromised by trying to convince voters with festivals laced with beer and sausage handed out for a "signature of support" and with invented and template-painted slogans such as: "the coalition must win so that Poland will not lose" - recalls the Speaker of the Sejm.

Przemysl houses, stores, Ruchu kiosks literally disappeared under stick-on posters. It was a real battle. At the election headquarters, water and flour were mixed to replace the real glue. Dozens of people went to the streets and tried to hang leaflets in the most visible places. It was not easy. Some of the site owners were afraid of the authorities, they tore down the posters themselves and called the militia. Security patrols appeared in the city and destroyed the posters. Of the 4,000 Solidarity placards and banners, they tore down about 3,000! Solidarity flags were also torn down, and people claiming to be employees of the city hall's department of commerce forced managers and shopkeepers to take down posters of the freedom side from store windows. The Solidarity election announcements were also destroyed in Jaroslaw, Przeworsk and Lubaczow.

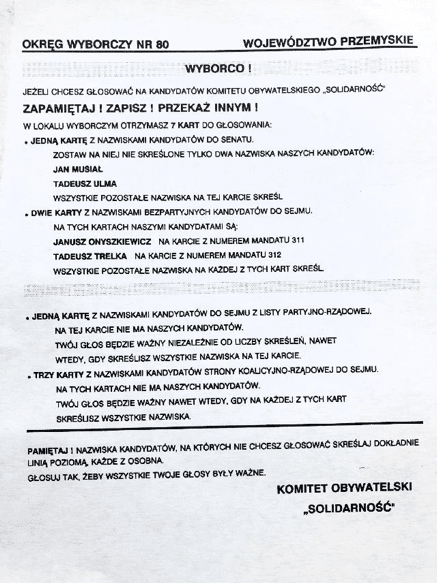

In the election campaign, the Civic Committee focused on education in the field and openness to citizens. The intelligentsia, people of culture and the Church were involved. Solidarity was presented as a team with common goals. To avoid divisions, as many candidates were appointed as there were seats. For citizens accustomed to voting for the "one and only right candidate" from the PZPR, the KOS prepared manuals on how to vote. In the election bulletins it was appealed among others: to the citizens to support the opposition, because "you owe it to them, because support for them means the end of murders, political rapes, suffering...". .

The poster war reached its climax the night before the election. The Solidarity side was determined. All night long, almost until dawn, people were sneaking around backstreets, under windows, and in backyards, secretly posting election announcements. Big cities like Warsaw got famous posters with a sheriff who instead of a star has a Solidarity badge in his lapel. However, it did not reach Przemyśl. Instead, there were other leaflets and announcements, which were hung wherever they could. They were also hung where they could not.

In the early morning of Sunday, 4 June 1989, the polling stations were opened. The voter turnout was not very high - over 10 million Poles out of 27 million eligible to vote did not vote. It was a result of apathy of the society, which did not believe that the election could change anything. In the whole country the mood was calm, there were no riots.

Cut off from the polls, with airtime of half an hour a week, the opposition did not quite believe what was about to happen: of the 161 seats in the Sejm available in free elections, it won 160 in the first round, with the remaining candidate advancing to the second round. Of the 100 Senate seats in the first round, Solidarity's candidates filled 92. In the Przemysl province, four candidates entered parliament: Jan Musiał and Tadeusz Ulma for the Senate, Tadeusz Trelka and Janusz Onyszkiewicz - for the Sejm. Despite such enormous social support, Solidarity was too weak to hold the reins of power on its own. Despite so much effort over many years, the people of Solidarity were unable to bear the burden of change.

Marek Kaminski says today: I appreciate the bloodless leading to the elections, but with such strength, advantage, and social support, Solidarity should have set conditions. I resent this very much. Solidarity was weak and controlled by the communists. We also missed Wilczek's movement in '85. They lined up their people, they pushed the secret police into companies. During meetings, including with Walesa, whom we treated then as the only leader, I never imagined that these were people who would go into alliances with the communists. I am ashamed that I sat with them then. We wanted independence, the Polish People's Republic was not an independent Polish state. How were we supposed to feel when we elected Jaruzelski as president of Poland? - says Kamiński.

Jan Karuś, the head of Solidarność Rolnicza (Solidarity of Farmers), also speaks of the events after 1989 in a depressing tone, describing the political turmoil and enfranchisement of the communists on national property.

Elected deputies and senators were also failing. In "Spojrzenia Przemyskie" (Views from Przemysl) from December 1989, Marek Kuchciński wrote about dissatisfaction and impatience of the society ignored by the authorities, lack of intelligence and helplessness.

However, no one regrets that effort. Those who went to the polls on June 4 simply wanted to overthrow communism. They succeeded, but the changes did not come easily, and we are still reaping the consequences of the negligence of that time.

- After 1989, we began to take responsibility for the state: at the level of local governments, state and local institutions. With the benefit of hindsight we can say that we did everything that could be done at that time. We expected changes in the state authorities and were disappointed, but this did not discourage us from work. From today's perspective it looks a little different: a small group of people performed miracles, fighting with communism like David with Goliath - recalls Marek Kuchciński.

Marta Olejnik